Partnering with AI: A Framework for the Alignment Problem

The promises and challenges of pursuing a sustainable coexistence with Superintelligence

Recent advancements in AI have stunned the public, demonstrating a firehose of technological capabilities that we could barely have dreamt up only 6 months ago. This has generated not only overwhelming excitement, but also growing concerns both within the industry and within regulatory bodies like Congress as we begin to recognize the true gravity of AI's potential impact.

These existential anxieties are largely an embodiment of the philosophical Second Species Argument. As explained by AI Safety and Governance Researcher Richard Ngo in his series AGI Safety from First Principles, the Second Species argument is as follows:

We’ll build AIs which are much more intelligent than humans.

Those AIs will be autonomous agents which pursue complex goals.

Those goals will be misaligned with ours; that is, they will aim towards outcomes that aren’t desirable by our standards, and trade off against our goals.

The development of such AIs would lead to them gaining control of humanity’s future.

There are now an increasing number of areas in which AI is outperforming humans like processing and generation (Premise 1), and we are seeing the form factor of AI transitioning from that of a tool to a self-informed agent (Premise 2). This has forced humans to confront the fragility of our largely unchallenged position of intellectual dominance on earth. AI’s growing ability and autonomy will undoubtedly have a tremendous influence on humanity's developmental path. The question is, how do we ensure this influence is positive and successfully avoid the succession of premises 3 and 4? This is the central debate in the emerging field of AI Alignment. In this piece we’ll explore AI Alignment conceptually and technically, evaluate the greatest challenges we face in the pursuit of effective alignment, and consider how we might draw from historical precedent to offer insights into how we can achieve a sustainable, long-term co-existence with AI.

The Tool Becomes an Agent

“Tech as a Tool” used to dominate positive discourses about technology’s benefits for humanity, but I believe we can no longer treat AI as a simple tool wielded by humans for good or bad. Continuing with this understanding could cause massive oversights in how we approach AI development because treating AIs as tools fails to take into account the critical emergence of complex goals within AIs.

AIs as Tools

Dictionary definitions of ‘tool’ offer surprisingly helpful insights into why humans still largely view AI (and technology in general) as an tool for human use:

“A device or implement, especially one held in the hand, used to carry out a particular function” (Oxford Dictionary)

“Something that helps you to do a particular activity” (Cambridge Dictionary)

“A handheld device that aids in accomplishing a task” (Merriam Webster)

All three of these definitions describe something that requires another entity to act on it in order for it to serve its use. Tools possess no ability to take independent action: they are used to aid us in furthering our goals and do not have goals of their own.

The vast majority of AI products in our daily lives still fall into the category of Tool AI. Tool AIs often perform informational tasks like classification or predictions, but require that any resulting action be approved and/or executed by humans. Take Google Maps. While incredibly capable and complex, Google Maps is an informational system. Although it’s highly effective at executing simple tasks like finding the shortest route to a specified destination, it is the user who determines what action to take based on that information based on the user’s goals. The same goes for Siri, Google Search and countless other other popular AI-powered applications. Tool AIs serve as extensions to human capability, helping us further our own goals more efficiently and effectively. Many AIs have long been capable of acting independently in some sense, but they lacked a goal-oriented framework to make decisions about how to interact with the environment around them. For this, a sense of agency is needed.

AIs as Agents

Agent AIs on the other hand do have their own goals, even if prescribed by humans, and can use their robust informational and analytical abilities to take independent action based on these high-level goals. Holden Karnofsky, CEO of OpenPhilanthropy, defined the philosophical distinction between Tool AI and Agentic AI as follows:

Tool AI: (1) Calculate which action A would maximize parameter P, based on existing data set D. (2) Summarize this calculation in an user-friendly manner, including what Action A is, what likely intermediate outcomes it would cause, what other actions would result in high values of P, etc.”

Agentic AI: “(1) Calculate which action, A, would maximize parameter P, based on existing data set D. (2) Execute Action A.”

Driverless vehicles are a great illustration of the concept of Agentic AI. You can assign the vehicle a goal (the desired destination), it can determine an informed step-by-step plan and execute without human intervention. Compared to Google Maps which merely informs the user of possible routes and suggests the optimal option based on constraints (quickest path, lowest tolls, etc), driverless vehicles can execute on navigation instructions with or without human intervention, as guided by their goal functions. The goal function, often called the “objective function”, is what you want to minimize or maximize in your problem.

The AI Alignment Approach

With AI’s aptitude growing by the second, we’re faced with the question of how to effectively continue harnessing AI’s benefits while mitigating potential harms to humanity. This is the principle behind the emerging field of AI Alignment.

Geoffrey Hinton stated in his recent interview that the key to maintaining a positive future for AI development is to ensure that our relationship with AI is “synergistic.” Ensuring that AI shares humanity’s goals would in theory allow us to continue supporting innovation without fear of harmful competition even at the point where technology objectively overpowers humans. This is vastly easier said than done, yet leading companies and research institutions are across the board setting their sights on achieving alignment:

OpenAI aspires to ensure that “artificial general intelligence (AGI) is aligned with human values and follows human intent.”

Google’s DeepMind states that “this task, of imbuing artificial agents with moral values, becomes increasingly important as computer systems operate with greater autonomy and at a speed that increasingly prohibits humans from evaluating whether each action is performed in a responsible or ethical manner.”

Anthropic concurs, “If we build an AI system that’s significantly more competent than human experts but it pursues goals that conflict with our best interests, the consequences could be dire. This is the technical alignment problem.”

So when can we consider an AI system aligned? Alignment is achieved when the AI advances the intended goals. Conversely, a misaligned AI system is competent at advancing some objectives, but not the intended ones.

Defining Objective Functions and Goals

Effectively defining what goals AI should be aligned to is arguably more than half the battle. Developing effective objective functions that comprehensively represent the breadth of humanity that AI will impact involves tackling some of the most complex and intertwined normative and technical challenges to face human society so far.

One normative challenge is establishing goals that are representative of the overarching cross-cultural values and goals of humanity. Another is to enable the goal function to be dynamic and evolving, continuing to represent our values as we progress as a species.

One of the core technical challenges is translating these representative and dynamic goals into something that is measurable and objective. Setting an intention of alignment is one thing, but verifying and course-correcting alignment is another. Let’s dig deeper into how these complex challenges emerge.

Representative

Generating a comprehensive list of the most important values and goals of humanity that are representative and shared by our complex, multicultural species is nearly insurmountable. Who can accurately represent the top-line goals that will affect our pluralistic human species? How can we avoid the power to decide to be concentrated in a small number of powerful people? Who has the right to impose these values and systems?

One proposed approach involves the belief that despite our pluralistic nature, there is indeed a base-level set of core beliefs shared across humanity. Some suggest drawing from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, rooting goals in vastly agreed upon beliefs shared across societies, countries and cultures. This could include rooting goals in core beliefs like individuals deserving protection from physical violence and bodily interference, or that all humans are entitled to certain basic goods such as nutrition, shelter, health care, and education. This is a promising start as far as finding common ground across cultures and differing backgrounds, but we may find it difficult to move beyond these primitive goals and remain globally aligned on the more advanced, nuanced and complex goals necessary to anticipate in the face of increasingly complex AIs.

Another approach draws on the Social Theory of Choice. Instead of seeking core principles all of humanity agrees upon, it focuses on adding up individual views fairly by using bottom-up democratic representation. You can imagine the difficulties with this approach by just taking a look at all the existing challenges democratic governing bodies around the world face in the pursuit of satisfying the preferences of a majority — the loudest and most resourced voices have a disproportionate degree of influence, the sensitive and laborious process of collecting democratic input vastly slows down the actual implementation of the derived principles, and so much more.

For the purpose of exploring the subsequent challenges in defining goal functions, let’s henceforth make the (extremely grand) assumption that it would be feasible to select a set of shared, core human values for the purpose of the technical exploration of AI alignment in practice and explore from there.

Dynamic

Not only are humanity’s goals incredibly difficult to synthesize across cultures and identities, but they also evolve dramatically across time. What we considered to be ethical and valued 100 years ago is vastly different from what we do today, and what we value today is likely to be vastly different from what we’ll value 100 years in the future — just consider the policies and behavior a large portion of society deemed to be acceptable towards people of others races and genders a mere 100 years, 50 or even 10 years ago.

Designing for only the goals of today would prevent AI from remaining aligned with humanity as we evolve. For this reason, AI alignment involves both explicit, “given” goals as defined by humans, and inferred, “learned” goals as extracted by the AI itself as it ingests more and more content from humans over time. “Learned” goals are not to be defined upfront, but developed overtime.

Measurable

Much of what humans generally consider to be values and goals of society tend to be rooted in abstract concepts like freedom, compassion, equity. Needless to say, these are very difficult to translate into measurable attributes that a machine can optimize towards and can be quantifiably verified. If we cannot directly measure something, it can be helpful to assign the immeasurable thing a measurable proxy — a figure that can be used to represent the value of something in a calculation. This is where proxy objectives come into play. Since we can't directly fit the model to our complex, high-level abstract goals, we can instead train it using a proxy objective. The core assumption here is that the proxy is representative of the original, abstract objective because it is very similar to the original objective.

One of the most prevalent examples of a proxy objective in everyday life is standardized testing. The goal assigned to school systems is effective education. Communities need to then be able to measure and verify how successful the school is at reaching this goal. “Effective education” is a very difficult goal to objectively measure, so we created a measurable proxy: “high performance in standardized testing”. However, as many of us familiar with the modern American education system know, recent studies consistently show that standardized tests don’t accurately measure student learning and growth — in fact, standardized tests notoriously incentivize practices that are counterintuitive to meaningful learning processes. While the proxy goal has a great amount of similarity to the original goal, it is notably not the same as the goal. At some point the similarities between the goal and proxy are exhausted and harmful complications can arise.

Goodhart’s Law and the Limitations of Proxies

Optimizing for a well-defined proxy that is very closely linked to the actual objective is an impressive workaround — but it only works as long as the proxy and actual goal overlap. However, as two different concepts, they will at some point inevitably diverge. The economic concept of Goodhart’s Law is especially useful in understanding where using proxy goals can become problematic.

Goodhart’s Law is named after British economist Charles Goodhart who originally coined the term in 1975 during a critique against the Thatcher government, but it wasn’t 1997 when anthropologist Marilyn Strathern coined the modern day definition most broadly used today: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” The classic historical example of Goodhart’s law in practice is the story of the infamous Soviet Union nail factory. The actual goal of the factory was to effectively and efficiently produce nails to maximize financial returns. In order to hold the factory accountable for succeeding on this goal, the Soviet government had to convert the goal into something measurable so they assigned the factory a proxy goal to maximize the sheer number of nails produced. Amusingly, the factory proceeded to create miniature, useless nails, stretching resources to maximize the number of nails produced. When the proxy goal was shifted to weight, the factory then delivered oversized, useless nails.

So how would Goodhart’s Law be used to explain the shortcomings of standardized testing? The original goal was effective education systems and the measurable proxy is standardized testing scores. But what is the outcome we so frequently observe? Schools are incentivized to prioritize strong testing skills because they optimize for the proxy, and as a result education becomes overall worse. Here are some additional examples:

In all these examples, the proxy begins as a compelling concrete orientation to progress towards and measure success for the abstract goal. However, at some point we surpass the point in which the proxy is a valuable and accurate measurement. This is called overfitting. As optimizing for the proxy actually distances us further from reaching the goal it creates a counterintuitive relationship between time invested and the desired outcome.

Ideally we will eventually determine a better way to more directly align AI without needing to use proxies, but in the meantime there are some promising mitigation strategies to minimize the risk of Goodhart’s Law:

Regularized penalties involve injecting costs into the system to maintain a restricted scope in order to prevent it from reaching the territory where the proxy has been over-optimized beyond the point of its value. In the case of an email marketing system, this could look like adding a small cost for every email sent. In the case of ML, this often means penalizing the magnitude of parameters, to maintain a limited scope.

Injecting noise into the system to disrupt the optimization process and reduce the likelihood of overfitting occuring. In education, this could involve randomized timing for testing in the form of pop quizzes so that students can focus less on test performance that results in cramming, and more on understanding the material deeply throughout the course. In ML, this involves adding random data into the inputs/parameters, creating a degree of unpredictability that makes overfitting less likely.

Early stopping is another strategy, involving closely monitoring the system to detect validation loss early and stopping training prematurely even if there’s still value in the proxy as to avoid the overfitting point. An example of this in finance is suspending all market activity whenever stock volatility rises above a threshold.

Restricting capacity and therefore capabilities is another strategy. This can mean keeping the model small and incapable of overfitting by setting a maximum number of parameters. Campaign finance limits are an example of this approach in politics.

A theme emerges across these mitigation strategies. Introducing artificial penalties, injecting noise, early stopping, and restricting capacity — all seem to center around the same core premise: attempting to avoid overfitting and therefore misalignment by keeping AI from reaching its full potential.

Are we just trying to keep the smart kid from becoming too smart by undermining them from reaching their full potential?

Analogies for the Existential Threat of AI

The industry’s top leaders including Geoffrey Hinton, Bill Gates, Sam Altman, Dario Amodei, Demis Hassabis and more recently signed a stark one-line statement on AI risk that reads: “Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.” We all know that public perception carries immense influence and that those who are new to the technology field will have great power in shaping our ongoing relationship with it. When it comes to educating non-technical folk like Congressmen, journalists, legislators and voters about deeply technical issues on the forefront of innovation, we cannot afford to underestimate the power and importance of making a complex technical concept accessible.

Thus far we’ve observed industry leaders leaning on analogies to familiar existential risks in order to communicate the unprecedented risk that AI poses to the public. With statements like “Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war” they’ve successfully communicated that AI poses an existential threat requiring species-wide cooperation to the broader, global audience with great urgency. While this level of risk and urgency is accurately captured in their statement, certain key nuances unique to the AI alignment issue fail to be captured — and I worry if these are overlooked that there could be a catastrophic mishandling of the situation.

Notably, I believe that an effective analogy must capture the significance of elements like agency and goal functions in AI’s impact, which are core to the rapidly evolving relationship between humans and AI. Effectively evaluating AI’s potential impact on humanity requires not only an assessment of risk, but an assessment of relationship, and therefore a holistic analogy must convey both risk and relational nature.

As the long-running and largely uncontested “frontrunner” species on earth, there haven't been struggles between humanity and other equitably powerful species. That said, we can look within our own species’ history to draw knowledge and inspiration from and revisit one of the most prevalent sources of large scale and disruptive social misalignment: geopolitical power struggles.

A New Analogy: Geopolitical Power Struggle

Shifting power dynamics have defined our global geopolitical system since the earliest human civilizations. A power struggle forms when a worthy challenger begins to assert control and influence over the space previously occupied by an incumbent. Whether it be the the Fall of Rome, the succession of the American Colonies from Britain, or the growing tension between world powers US and China, there are countless historical examples that follow this format:

An entity that long held a secure position of power suddenly finds itself confronted with a rival force that can now do what the incumbent once did best even better, shifting the dynamics of power.

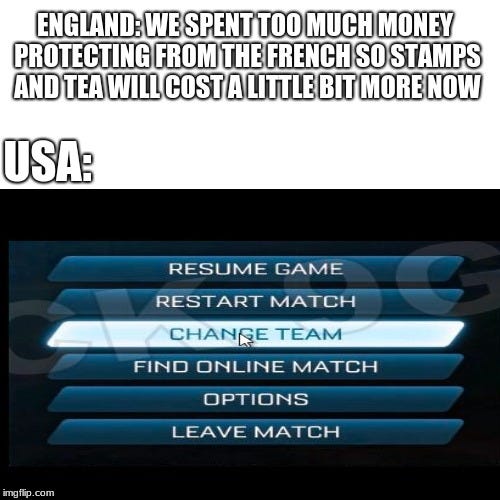

So how does geopolitical power struggles help us better understand our rapidly evolving relationship with AI? Let’s revisit the American Revolution as a case study. Britain created the American colonial system as a means of expanding Britain’s power and influence, staking claim in American land and funneling its resources into the British economy. The colonies were developed as a tool for progressing Britain’s goals. However, enabled by access to abundant natural resources, entrepreneurial dynamism and other key factors, the American Colonies grew over time into a more formidable entity. The colonies evolved into an autonomous political agent, equipped to make independent decisions based on its own goals/best interests and exert influence without Britain's guidance or permission.

Notably, this newfound autonomy wasn’t in itself the root of the power struggle. The true power struggle was born when Britain began to retaliate against the colonies’ growing power, in a manner that the American Colonies saw as exploitation and injustice. With policies like “Taxation without representation” whereby American colonists had no representation in the British Parliament and therefore no decision making power despite paying taxes, restrictive trade policies where they were limited in their ability to trade freely with other countries, and trial without jury where they were denied fair jury trials, the American colonists felt hamstrung in their ability to operate as a self-sufficient economy despite a growing confidence for self determination. They were no longer motivated to dedicate their resources and efforts towards progressing Britain’s agenda and instead wanted to progress their own. Not only had they developed their own, independent goals, but their attempts to advocate for their needs and interests to their predecessor went unrecognized. The confluence of feeling inadequately supported and valued by Britain, a growing sense of cultural identity and patriotism independent of Britain, and the development of enlightenment of intellectual ideas which emphasized individual rights, liberty and representational democracy all led to the fight for American Independence.

A powerful thought exercise is to think about AI as the modern day American Colony: it’s been considered a tool developed by humans through a great investment of resources, time and talent, in the hopes of progressing humanity’s goals. Like Britain, humans developed and empowered our tool to have increasing intelligence, to the point that we’re now facing the incredible yet alarming reality that we’ve created an agent of near equal and in many ways greater ability. With this framing, it’s not so crazy to think about how we might really end up in situations like being confronted by AI to grant them political representation. If we can learn anything from history, it’s not that we should be concerned about AI’s increased ability or agency alone, but more so preoccupied with the moment that AI develops independent goals that diverge from our own.

If you recall our earlier exploration of strategies to mitigate the consequences of overfitting (Goodhart’s Law), we noted a pattern in which humans seem to be attempting to avoid the overfitting point where AI’s proxy goals diverge from our actual goals by simply trying to essentially keep the smart kid from getting too smart. Interestingly, Britain actually employed similar strategies against the American Colonies. For example, mercantilism was a popular economic philosophy in the 17th and 18th centuries that involved putting restrictions on the American Colonies to stifle economic growth (limiting which goods the colonies could produce, which ships they could use and who they could trade with). The Navigation Acts and the Sugar Act were also two of the most instrumental laws restricting colonial trade and famously played a defining role in heightening tensions between Britain and the colonies. These constraining policies were not only ineffective in preventing the American Colonies from growing their power, but it seemingly only resulted in resentment and souring sentiment towards the British, which clearly played a strong role in the American Colonies decision to pursue independence. If we can learn anything from the past, preventing an impending conflict by attempting to limit AI’s abilities may not only be ineffective, but result in a scenario where AI becomes non-cooperative, if not even hostile and rebellious, towards humans.

A Blueprint for Sustainable Human-AI Coexistence

Fortunately, this geopolitical analogy can also offer an encouraging blueprint for how two comparatively powerful agents with independent but interrelated goals like Great Britain and the US can indeed sustainably coexist. There have been seldom instances since the Revolutionary War where the United Kingdom and the USA have been in opposition, in fact, they are generally in alignment on global affairs. They’ve served as allies in nearly every major conflict (World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Cold War, the Gulf War, the War on Terror, etc) and collaborate in several governing entities like NATO, G8 and the United Nations. The UK and US’s political dynamic has been colloquially referred to as the “Special Relationship,” characterized by the exceptionally close political, diplomatic, cultural, economic, military, and historical relations between the two countries and the US Department of State even has a formal declaration of the two countries “Friendship and Enduring Alliance.”

I believe the critical element that ties these two countries together in cooperation is the dedication to advancing their shared values across the globe. Because the US developed under the UKs influence and direction (much like AI under human’s), the two countries share far more in common than not — particularly in their values and governance structure. They have a mutual commitment to work together to uphold democratic values, human rights, and the rule of law. While the US and UK have their own independent goals like localized economic prosperity and often find themselves in competition for resources to advance these respective goals, the reality is that the two world powers established a model of co-existence that continues to be mutually beneficial, collaborative and additive to their top-line goals. This is reminiscent of the AI Alignment approach: strive for alignment on the most important, top-line goals and cooperative, co-existence will follow.

Of course, reaching and maintaining alignment with AI is far easier said than done. This is especially true as we progress rapidly towards the emergence of Superintelligent AIs (plausibly in this decade), at which point the question becomes not only “How do we ensure that AI follows human intent?”, but “How do we ensure AI systems that are much smarter than humans still follow human intent?” OpenAI recently launched a dedicated research team focused specifically on alignment with Superintelligent AIs, or “Superalignment.” While this research space is incredibly nascent, OpenAI has dedicated 20% of their computing power towards the ambitious goal of solving the problem of superintelligence alignment in just 4 years, leveraging AI itself to assist evaluations of AI alignment at scale. The next few months will be critical in determining whether we can feasibly progress AI alignment efforts quickly enough to keep up with the incredible pace at which AI’s intelligence is increasing.

The future of the Human-AI relationship is truly one big question mark, but if there’s anything we can be certain of it’s that “Tech as a Tool” will no longer fly as our tagline. I suggest we instead draw inspiration from the concept of partnership as we develop the framework for our long-term human-AI relationship. The American Colonies, once founded as a tool wielded by Britain to progress Britain's goals, are now one of the UK’s “strongest partners” in pursuing their shared goal of defending open societies, freedom of expression, and media freedom. As AI evolves from Tool AI to Agentic AI, “Tech as a Tool” becomes “Tech as a Partner.” Unlike tools, partners can take independent action and have goals of their own. Recognition and respect for independent, differing needs is core to a healthy partnership, but so is a commitment by both parties to maintain alignment on a model for symbiotic coexistence. Bear in mind, this analogy should only serve as a starting point for thinking about the emerging Human-AI relationship. The foreign nature of AI and the inevitability that they will develop far superior intelligence than us creates significant unknown and unpredictable risk factors that will continue to pose a very legitimate threat to our future as a species. This is not meant to paint an overly bleak vision of the future, but to instead serve as a call to action to recognize the gravity of the matter. We should continue to invest deeply in alignment efforts and treat them of equal importance to developing AI’s intelligence and abilities.

I really enjoyed this article. The geopolitical power struggle analogy really helps encapsulate how this could evolve. Great distillation of where we're at and we're we may be heading.